Behind Closed Doors – Robin King

In 1942, Tom Matchett started work at ‘Coates the Butcher’ in Borrowash.

He was 15 years old and the Victoria Avenue business was a popular fixture in the village with a growing reputation for service.

It was a good start for a local boy – but would not have been entertained for the likes of Robin King; seven years younger and also a resident of Borrowash.

As Tom saw it:

Robin King’s father was Sir Robertson King; he was the Chairman of the Electricity Board and used to be driven to work at Ilkeston every day in a massive Bentley. He came up Station Road and then Victoria Avenue on his route. I worked for Don Coates in the village and it seemed that he and all the other retailers made it their business to be at their shop doorways at the appropriate time in order to raise their hats and hopefully curry his favour and patronage. Makes one sick to think about it.

Robin was invariably a passenger in the car (a Rolls Royce not a Bentley) with a different perspective:

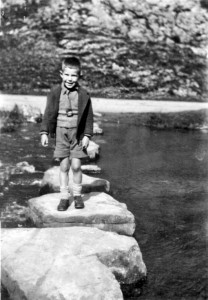

I did the ‘milk round’ in the Rolls with the chauffeur, Duncan Burroughs. It was 1939 Rolls and we had the use of it from new until nationalisation. The ‘milk round’ was the weekly delivery of eggs, butter, milk and cream to friends and relatives. My mother would bottle all the milk and make all the cream and butter and then parcel it all up and place it in the back of the Rolls – floors and seats – and in the boot. I always sat in the front. When we got to the first address, I’d leap out and make the delivery and then we’d be on our way to the next.

The Kings lived in the prestigious Station Road Riverside House, courtesy of the Midlands Electric Supply Company where Robertson King was employed as Manager. The glamour of the car and chauffeur that also came with the job seems to have gone to Robin’s head:

I remember, to my shame, giving the royal wave to anyone I knew that we passed in the village. Johnny Morris, who lived at the bottom of the drive, called me a ‘stuck up little sod’ the next time he saw me after being on the end of the royal wave. I didn’t know what that meant, so made the mistake of asking my mother.

It was a case of parallel lives within the same village.

The Kings were philanthropic and the children, Gil and Robin, got used to their toys being given away to needy families.

When local traders doffed their caps to the passing Rolls, Robin considered it to be:

A routine thing for all the villagers. I took it not as deference, nor even respect, but just as a friendly acknowledgement.

Seventy one years later, Tom Matchett’s feelings are more akin to resentment:

As youngsters, we used a steep grass bank behind Borrowash railway station and backing onto his property as a downhill, both winter and summer and this was very much to his annoyance.

In fact, Robertson King called upon the assistance of Frank Smith to use the Wesley Youth Club to try and stop this activity. Frank Smith was Leader of the Youth Club, Clerk to the Parish Council and conveniently, a clerical worker at the Electricity Board Offices.

Still a case of who you know and not what you know.

Robin King and Tom Matchett came from the same village.

They might have come from different worlds.

While Tom’s grandfather was a labourer and his father worked as a cotton spinner, Robin’s forbears hailed from backgrounds that were comfortable if not lavish.

Grandmother Harriet (1867-1943) came from Ketton and was the ninth of Sarah and Edward Dunfords’ eleven children.

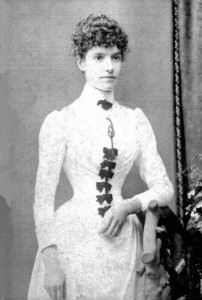

It was not a privileged background, but an early photograph of Harriet taken eight years before her marriage shows a young woman with a confident air.

After a period at home, looking after her parents, she took a job as Housekeeper at Weald Hall in Potters Bar, Essex where she met her future husband.

Frank Latimore was the Head Gardener and they married in 1893.

The couple and their daughters Kathleen and Dorothy (Robin’s mother) re-located to Nottinghamshire and Frank was employed as Head Gardener at Trowell Rectory.

They finally settled in Ilkeston where Frank worked as an Insurance Agent. The Latimores bought a house at 63, Heanor Road in 1920 and it was to remain Frank’s home until his death in 1950.

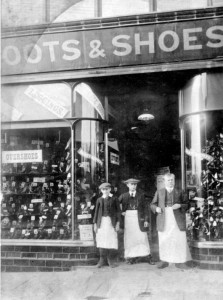

Robin’s father was the eighth child of twelve born to William King, a shoe shop manager from Birkenhead and Letitia Moody, a Shropshire teacher.

Robertson King’s knighthood was the culmination of a prestigious career, but his siblings were no slouches, boasting two Oxford degrees and careers as a headmistress, headmaster and chemist. One brother emigrated to Canada.

In Ilkeston, William Smith became Manager of ‘S. Smith, Boots and Shoes’ and the children went to Ilkeston School, where in 1909, aged 14, Robertson met the 12 year old Dorothy Latimore.

Years later, in 1944, eight year old Robin King was to spend seven months confined to bed in Riverside House, diagnosed with suspected TB of the stomach glands.

To while away the hours and days between blood tests, he wrote a short story, typeset by Uncle Harold, the headmaster.

‘The Runaway Children’ was based upon a childhood escapade and in itself amounted to very little, but interest remains in the name.

It was written under the pseudonym of Guy King. That was strange in itself as I had no knowledge at that time, of my Uncle Guy, who I was named after and who was killed in Gallipoli in September 1915. He was also the man my mother would probably have married if he had lived, rather than his younger brother.

The First World War impacted upon members of the same family in different ways and almost at random.

Harold, the eldest King brother had the luck of the draw.

In 1914, the assistant teacher at Nottingham’s Whitwell School joined the Sherwood Foresters regiment.

He did not go to France with the first-line Territorials but was posted to Dublin with the 2/8thBattalion to suppress the Irish Republican uprising in the city.

Harold excelled in service and was awarded the Distinguished Conduct Medal for his actions. The official citation published in the London Gazette on 24th January 1917 read:

For conspicuous gallantry and devotion to duty, during operations in the Irish Rebellion of 1916. He greatly assisted his company commander during the storming of various buildings. He set a splendid example throughout.

His comments in a letter to a Whitwell teaching colleague, reported in The Worksop Guardian, 2nd March 1917 show that he viewed his eventual posting to France (26th March, 1917) with trepidation:

Personally, I’m not particularly anxious to go (I think no one is). I had quite as much as I want in Dublin

but he declares himself prepared, like most of us, to go quite cheerfully, and leave the outcome on the knees of the Gods.

Things worked out for Harold who returned home and enjoyed a successful teaching career before dying aged 79, in 1972.

Guy King, his younger brother, was a member of the 1387 Communication Troop, 1st South Notts Hussars.

He kept a diary from January 1915 to 19th August, initially from his depot at Cley Next-the-Sea, Norfolk.

Life is civilised and riding school, horse inspection, shooting and map reading are interspersed with holiday in the afternoon, whist drives, concerts, singing and dancing.

The troop eventually boards ship and sets sail for Alexandria on 11th April 1915, but the tempo is more tour ship than war ship!

Thursday, 15th April: We go through Gibraltar in the night. Am disappointed at not being able to see the rock.

On arrival, Guy records:

Sunday, 25th April, 1915: We disembark and have to march to camp. Have a very exciting time.

He is amused by the fact that bicycling in a desert doesn’t work, but declares that Alexandria (or ‘Alexander’!) is a grand place.

In between practising signalling, there are many easy times, good afternoons; the barracks at Cairo is a fine place, we look like being comfortable and the only cloud on the horizon is a slight indisposition owing to eating nothing but biscuits the day before.

Saturday, May 22nd is a red letter day:

Went to see the Pyramids. We went in a carriage about ten miles and went inside Takhara pyramid and then rode on a camel to the Sphinx and went inside the temple. Had a very interesting time.

By mid June, signalling and church parade have given way to some real action.

Guy emerges unscathed from a mounted attack in the desert, no thanks to his rotten horse,takes part in various other successful battles and digs trenches in the desert.

The Brigadier compliments good work with the telephones and there is a perceptible ‘feel-good factor’ with the team working and playing hard:

Saturday, 10th July: Went on a regimental trip up the Nile. Had a very good time and went to Kursal at night.

Tuesday, 20th July: Take up quarters at Ksara el nil Barracks. Full of bugs but pleasantly situated on side of Nile. Mess orderly but have native boy to do work.

On Saturday, 31st July, an evening at the cinema has a disconcerting ending:

When I came out, I saw a fire engine and a glare in the sky. Went to see what it was. The Warra had been set fire to by Australians. There was about half a dozen houses burned down. Houses looted and South Notts Hussars had to turn out mounted and armed to quell the mob. I had some cigarettes out of the scuffles.

By mid August, the squadron sets sail for the Dardanelles and an ominous note is sounded when a drunken stoker dives from the stern and is drowned, leaving a wife and six children.

Monday, 16th August provides the last of the sight-seeing observations:

All day passing through the Greek Archipelago – lovely islands on both sides of the boat.

Two days later, from Lamnus (the naval base for the Dardanelles), the mood is set:

We had a busy day. The Turks shelled us all day and night and there were about 12 killed by shrapnel and a transport was struck.

The diary ends in foreboding style:

Thursday, 19th August, 1915: Had a fright when going for water – shrapnel went straight over my head and dropped a few yards in front of me.

Stanley Guy King was killed in action on Sunday, 5th September 1915.

The brigade had been ordered to capture a communications trench (later discovered to be a main Turkish position) and set off from Chocolate Hill. Movement was in order of squadron: first the South Notts Hussars, next the Sherwood Rangers (with orders to deploy to the left) and finally, the Derbyshire Yeomanry (with orders to deploy to the right). During the advance, the order was changed for the Derbyshire Yeomanry to deploy to the left instead of the right, but it did not reach them and the squadron marched straight into heavy fire.

Regimental padre, Father Day, buried Sergeant Holden of the Derbyshire Yeomanry and Private SJ King of the South Notts Hussars, but the Turks landed a shell directly on the new grave.

After that, burials were held either after dark or just before dawn.

On November 3rd, 400 men, the rump from 5,000 – took five hours to march the four and a half miles from the pier to the rest camp.

Guy was awarded a posthumous Victory Medal and his name appears on a memorial in St Mary’s church, Ilkeston; a casualty amidst so many others, of World War One.

The news of his death was devastating for Dorothy Latimore, at the time studying to be a teacher at University College, Nottingham.

Her old school friend, Robertson, Guy’s younger brother, had gone to war himself and sent her a postcard from his basic training camp in 1915.

The postcard is a photograph of the Sherwood Foresters Regimental Band and Robertson is the bass drummer.

On the back of the postcard he makes a self deprecating comment about his suntan, adding:

I wash regularly, so no sarcasm!

Another photograph of him in uniform continues the theme:

Don’t write and send me some soap because it’s sun brown, not dirt, R

but a third picture from the family album shows soldiers constructing the defences for Château de la Haie and evokes a significant World War One milestone; the capture of Passchendale Village by the Canadians who subsequently had Christmas dinner at the Chateau

Robertson, like Harold, lived to tell the tale.

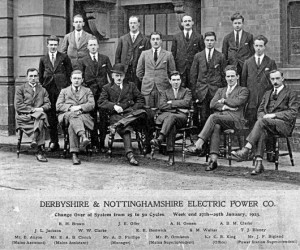

He returned in 1919 and took up the threads of life, completing his teaching qualification and then making a career change by taking a post as Office Manager at the Derby and Notts Electrical Power Company.

He rented a house, (47, Heanor Road, Ilkeston) from the company in 1923 and then bought it in January 1926 In September 1926, Robertson King married Dorothy Latimore but it was not a whirlwind romance. They had already known each other for 17 years and but for the vagaries of war, might never have married at all.

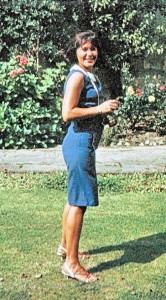

This photo was unidentified: there are no less than four copies in Dorothy King (Latimore) (1897-1986)’s collection, all in vaious staes of disrepair – this is the best. None of them are identified in any way. Generally, we believe that there is no doubt that this Dorothy King (Latimore) age about 15, dressed for a part in a Shakespeare Play.

The wedding took place at Nottingham Registry Office in September 1926.

There are no photographs and the whys and wherefores are a matter of conjecture for Robin:

Was she pregnant? Was marriage forced upon her because of social fear?

Mother always said she lost two babies (never specified miscarriage or stillborn) before Gil and two before me. Don’t know – just supposing….

What is incontrovertible is that by 1930, Robertson King was earning an annual salary of £2,000 as Deputy Manager (the equivalent of £378,000 in 2013) of Derby and Notts Electrical Power. In 1930, he rented Riverside House from Balfour Beatty, the owner of the company.

It was a large, virtually derelict house, requiring an enormous amount of work.

In September 1932, when their first child, Gilian was three months old, the Kings moved in.

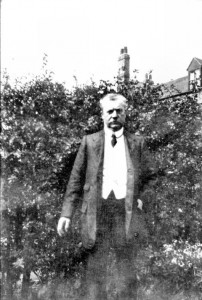

It was Robertson’s home until his death in 1976.

Riverside House was an imposing residence; beyond the imaginings of Tom Matchett and his friends, but entirely appropriate as the setting for Robertson King, who was appointed Deputy General Manager of all the Power Companies controlled by the Midland Counties Electrical Supply Company Ltd (or Midesco) in 1938, two years after Robin’s birth.

The house initially came with ‘staff’ – two maids, two gardeners and a nurse in addition to the chauffeur; nevertheless, Dorothy was indefatigable, scrubbing, polishing and, during wartime, virtually running a small farm.

According to Robin:

They acquired a herd of twelve cows, four pigs and 33 hens. Charlie (gardener) milked the cows, mucked them out and fed them in the winter. If he was not there for any reason, Mother did it herself.

She also did all the paper work associated with keeping animals. They have to have a birth certificate and a death certificate and a reason for the death. They have to be TB tested and all sorts of other things that I never knew about. Mother did all that too.

Sterilising the milk, bottling it, making cream, making butter – she did all that.

When she wasn’t running a home and deputising as a farmer, Dorothy King turned her attention to her husband’s business:

They never stopped talking to each other about all the details of his job and the people, and if he told her he was considering appointing someone to a position in the company and she didn’t agree, the argument would go on for days.

The marriage was very far from a fairytale romance; Dorothy had at least one lover; husband and wife never shared a bedroom and in the late 1960s, Robin, then married himself to Melody, was the recipient of a disconcerting request from his father:

He had a bedside cabinet with five drawers completely filled with back numbers of ‘Playboy’ and ‘Men Only’.

On one of my many visits to Riverside, he presented me with the whole load and asked me to get rid of them.

When Dad died in 1976, one of my first jobs was to empty my father’s bedside cabinet. Just as many as there were ten years earlier!

But the Kings were a brilliant business team and in Robin’s opinion:

He wouldn’t have got the knighthood without her and she really earned her Lady King.

Guy King may have captured Dorothy’s heart; but her head – and life, belonged to Robertson.

Riverside House itself was the love of Robertson’s life and his son felt the same way:

I loved that house as much as he did. I can rightly claim that I knew every shrub, every current in the river of all that 26 acres. I carried photos in my wallet when I went away to boarding school and then in the RAF, not of my parents, or sister, or girlfriends, but of that house and river. It was a happy house, never any rows, except where Gil was concerned – and no visible shortage of money. A wonderful spoilt childhood…

Robin was born in 1936 and early memories were inevitably connected with wartime.

His father was a staunch supporter of the Conservative Party and Robin recalls

playing in the front sitting room at Riverside under the watchful eye of my father who was listening to the radio. He suddenly got very excited and rushed out of the room shouting ‘Doll! Doll! Winnie’s got it!’ which must have been when Winston Churchill was appointed Prime Minister.

The cellar at Riverside was converted into an air raid shelter; Robin and sister Gil were ‘evacuated’ to a cottage in Ellaston, near Ashbourne.

Their Aunt Nellie was headmistress of a local school where they enrolled as pupils for the duration of the three month stay.

The house came with a garden and a rickety swing but that was not the most memorable feature:

There was a wooden – built outside chemical toilet, some yards from the house. I used to go in there every morning and entertain passers-by with my repertoire of songs: ‘There’ll Always Be An England’, ‘Kiss Me Goodnight Sergeant Major’, ‘Run, Rabbit Run’, ‘We’re Going to Hang Out The Washing on the Siegfried Line,’ and various Sousa Marches. Everyone always knew when I had finished, because I always beat time on the tin Elson container beneath me, except for the last song which was always ‘God Save The King’ and was sung standing up – so no drum beats!

Returning to Riverside meant attendance for Gil at the private Ockbrook Moravian School.

Her younger brother remained at home where there was no shortage of excitement including a hunt for an unexploded bomb:

I remember Dad coming into the cellar very late one night ( he was the local Home Guard Commander) holding a torch and saying to mother ‘Did you hear that? Three whistles and only two bangs.’

And he departed into the night, carrying a torch, looking for an unexploded bomb. Fortunately, he didn’t find it. It landed about half a mile away in Manor Park off Manor Road, Borrowash and was exploded by the Bomb Squad the next day. A large piece of shrapnel from that explosion came through the roof and ended up on the scullery floor at the back of the house- fortunately not occupied at the time.

1940 brought other changes.

With the death of AD Phillips, Robertson King was appointed Manager of the Electricity Group and acquired a company Rolls Royce, plus chauffeur; Duncan Burroughs.

There were changes on the home front as well.

Two American fighter pilots turned up and were billeted at Riverside; watched carefully by Dorothy. Gil appeared to be a little too keen on them but more importantly, their taste in music (predominantly Bing Crosby and George Formby) was not to Mrs King’s liking:

That’s not singing, that’s shouting.

In other ways, life proceeded as normally as possible in wartime, with holidays at Dovedale, based at the Izaak Walton Hotel, and a month in a cottage near to Hopton Hall; the home of one of Robertson’s professional contacts.

In 1941, Robin joined Gil at Ockbrook Moravian School.

He settled well, but at home, his mother held firm opinions about playmates.

Venturing any distance from the vicinity of Riverside House was frowned upon (think of your father’s position) and Dorothy’s determination to safeguard her son from potentially unsavoury friendships was vindicated when Robin asked her the meaning of a particularly lurid swear word and freely admitted that I’d learned it from Johnny at the bottom of the drive.

Predictably, maternal disapproval made such relationships all the more alluring, and Robin continued to play with the outlawed Stowers, Blavenges and Morrises; sometimes to disastrous effect:

One day, I was dared by the boys at the bottom of the drive to climb a willow tree on the river bank to the very top, stand with arms outstretched on the topmost branches and shout ‘Bugger Borrowash’ three times and then I could join their gang.

Task completed, it then remained to make the descent and here

I panicked and reached for a branch – and went straight down on my back and knocked myself out. Came round to find that they had formed a chain from the river and were passing water from hand to hand and then throwing it in my face. Fortunately, not much got to me or the water might have killed me. So we all went home – and I never told anyone. I didn’t realise it until quite recently, but that was the start of my back problems. The bottom two discs in my spine are fused together and have been for an indeterminate number of years.

The end of the war in August 1945 meant bonfires, fireworks and celebrations.

For the King children it also marked another milestone; leaving Borrowash and school in neighbouring Ockbrook, for boarding school.

Enrolment in a fee-paying boarding school denoted the difference between the boys at the bottom of the garden and the children who lived in the big house.

For Dorothy, overly conscious of her husband’s position, it was all part of a lifestyle that would lead to Sir Robertson and Lady King.

In reality, it was to spark a disastrous chain of events including a graphic court case reported in salacious style by The News of the World.

Gil’s life in particular, was to spiral dangerously out of control and the school that both children attended was forcibly closed.

Robin’s first school was the preparatory; Smallwood Manor in Staffordshire, a feeder school for Denstone College.

From the outset he was horribly bullied.

A senior boy took the mickey out of my accent and the name of the village where I was born. I was told that he had my name on his list for Pay Day and he would make sure I didn’t forget. He and his friends reminded me every single day of term. Pay Day was always the last day of term before parents came to fetch you home after lunch: older boys would collect up all the younger boys whose names had been noted during the term and take them into the woods surrounding the school. There you would be forced to drop your trousers and you would be caned severely.

In abject terror, Robin evaded his potential torturers on the last day of term and pleading sickness, hid in Matron’s Clinic.

Over the holiday, he begged his parents to allow him to leave and join Gil at her boarding school and to his amazement they agreed.

From what Gil had said, it sounded a much more pleasant place.

Robin does not disclose how much if anything, he told Dorothy and Robertson King about the bullying behaviour of the big boys from Smallwood.

Whether they would have objected to it anyway is a matter for conjecture.

Along with many people of their status and era, they might have regarded it as part of an essential ‘toughening up’ process.

In any case, there were other subjects that were off-limits.

As a four year old child, Robin accompanied his mother on a Christmas shopping trip to Nottingham. Dorothy left him standing outside a photography studio, specialising in child portraits while she visited a tobacconist.

Robin had strict instructions not to move but that did not protect him from a crude sexual assault by a tall man in grey overcoat and trilby hat and glasses. He said what a good little boy I was.

The frightened child kicked out at him; almost immediately, Dorothy returned and

We then spent the next 20 minutes or so chasing around Market Street looking for him, because my mother saw my upset and I told her what had happened – then I wished I hadn’t.

He did not feel able to tell either of his parents about the three sexual assaults I experienced between 1947-1952 by an older man on the train from Borrowash to Nottingham or admit to a similar attack from a son of one of Robertson’s employees, a boarder at Stowe public school.

It was a case of ‘least said, soonest mended’, and probably typical of the times, but when Robin met Jimmy Savile, many years later, he was not deaf to the warning bells.

During my time at Raleigh as Advertising Manager, one of my jobs was to act as the contact point for Jimmy Savile for all his various charity bike rides from Land’s End to John O’Groats.

Each time he did them, Raleigh provided him with a tailor – made racing bicycle, plus a spare, at a cost of three to four thousand pounds. And every time I met him, he made my flesh creep a little bit more.

When I met him, it was usually in London at the very large Chinese restaurant that used to be at the bottom of Edgware Road. When Jimmy was appearing on ‘Top of the Pops’, he would travel to London in his large Mercedes van in the back of which was a huge bed, plus kitchen and TV plus sound system. He would park it on the kerb opposite the restaurant so it became a signal to all who knew his habits that he was holding court within.

In the restaurant, he had a table which was raised on a sort of dais and if you visited, you always sat opposite, never beside him and any meeting at say, 8pm should not be expected to end until at least 10pm. And while you were there, a constant stream of other people would attend court with requests for Jimmy to do all sorts of work. Money was rarely mentioned specifically – just hinted at. Sex was never mentioned but the use of the bed in the back of the van was hinted at fairly often.

I always felt glad to get away when a meeting was finished….

Horsley Hall, a co-educational boarding school in Staffordshire was a ‘Freedom School’.

Like Dartington, (closed in 1987 after a spate of appalling publicity) and to an extent, AS Neill’s Summerhill; it eschewed traditional methods of teaching and relationships between staff and pupils were informal.

Attendance at lessons was optional and Robin sums the situation up neatly:

How my parents, both qualified teachers, fell for it, I do not know.

Horsley was run by the Headmaster, Robert Copping and his assistant, 27 year old Joe Reynolds.

According to Robin:

In the 18 months I was there, I learned absolutely nothing except how to smoke and swear.

There was also the matter of fending off the attentions of Copping:

He liked little boys and lost interest in me when I kicked him on the shins for putting his hand on my thigh

but in the 1940s, it did not occur to Robin or any of the other children to tell their parents.

Copping was just one of a long line of ‘authority figures’ ultimately leading to Savile, who operated ‘behind closed doors’, relying on position and power for anonymity.

Meanwhile, life proceeded as normal and the Kings continued to patronise Horsley; their own respectability and that of other parents of similar means, unwittingly providing cover for the exploitation and abuse of children:

Half term at Horsley. I was collected by Dad’s Rolls Royce, driven by the Chauffeur, Burroughs, with Charlie Charlton, the Gardener, sitting next to him.

Dorothy and Robertson King were watchful and attentive parents; but their concern for Gil and Robin’s safety was directed at the wrong targets.

Dorothy had been assiduous in monitoring Gil when the American airmen were billeted at Riverside and Robin was no stranger to her strictures about the evils of mingling with the local children.

Now in 1947, Robertson behaved like a typical paterfamilias, when his teenaged daughter requested permission to go to see Derby County play Charlton Athletic in the FA Cup Final.

Dad obviously thought it was not the place for young ladies.

He was not aware that his 15 year old was already a heavy smoker and deep in the throes of a sexual relationship with the 27 year old Deputy Head of Horsley, Joe Reynolds.

Matters then took a bizarre and troubling course.

On the one hand, Robertson King continued his inexorable professional rise, acceding to the blandishments of the ’45 Labour Government (and his mentor, Lord Citrine, an original founder member of the TUC) and becoming Chairman of the first East Midlands Electricity Board on the understanding that this would eventually lead to a knighthood.

On the other, he found himself in the role of parent to a delinquent daughter; embroiled to an increasing extent in the fall out from court cases, the eventual closure of Horsley Hall and a brawl with ‘The News of the World’.

The death knell for Horsley was not sexual abuse but financial ruin.

Gil, by now estranged from her parents and refusing to come home at all, was easy prey for Copping and Reynolds:

Copping was having severe financial problems with the school and Gil had told him that she was due to receive a large sum of money from her grandmother’s will (not true). A plot was therefore concocted for Copping to go to Riverside and ask formally, for her hand in marriage. He was, of course, refused.

Copping was well aware of Gil’s liaison with Joe Reynolds but Gil said it didn’t concern him because he preferred little boys.

In September 1947, Copping and Reynolds started a Junior School at Kibblestone Hall and appointed Gil as ‘Manager’.

She was now effectively providing ‘services’ for both of them.

The Kings, despite their money, prestige and professional standing, were essentially powerless; desperately ‘reacting’ to a situation that had already spiralled beyond their control.

Robin (who was removed from Horsley and placed as a day pupil at West Bridgeford High School) recalls an attempt by Robertson to rescue his daughter with disastrous effects, bordering upon pantomime:

Dad took his elder brother, (a Headmaster in Nottingham; Uncle Harold) with him and tried to take her back by force. A mistake. She won the fight and ran off into the woods and hid, leaving them with no alternative but to return to Riverside empty –handed.

This resulted in headlines in ‘The News of the World’ ‘Electricity Chief Assaults Daughter 15,’ (she was actually 16) and caused a virtual siege at Riverside House by press.

Dorothy’s usual instinct to protect her children from dangers outside the boundaries of Riverside kicked in and she forbade Robin to leave the house.

It was a forlorn hope.

I promptly disobeyed. I was in the middle of a long conversation with a man in a brown mackintosh I met on the drive by the side door, when mother suddenly crashed open the bedroom window: ‘Robin! Back into the house! NOW!’ and then proceeded to give the reporter a piece of her mind about talking to young children without permission; crashing down the window and disappearing before he had time to answer. Fortunately, she vented her spleen on him and was quite reasonable by the time she met me – although I was then banned from going out of the house at all.

With family life in turmoil behind closed doors, the outward ‘face’ of the Kings remained imperturbable.

Robertson was invited to join the board of Derby County Football Club by its then Chairman and owner, ‘Ozzie’ Jackson and 20th November 1947 saw Robin and parents celebrating the wedding of Princess Elizabeth and Prince Philip:

We saw the entrance of the coach from the Mall and the return journey after the marriage. We stayed at the Waldorf Hotel on the Aldwych (Dad’s regular hotel for business trips).

But on 7th April, 1948, a court judged Gil to be out of her parent’s control; she was made a ward of court and placed on probation under the eye of Dorothy and Robertson at Riverside House.

Attempts to impose structure and routine, by means of a book keeping and secretarial course at Derby Technological College were fruitless; as were all attempts at a curfew.

Robin says, with hindsight:

Gil would have caused trouble anyway- strong personality versus strong mother AND strong father

but as his sister took to visiting various places in Derby after Tech had finished, sometimes the cinema, sometimes the St James’ Hotel (‘Jimmy’s’), getting home after midnight the progress of events has an inevitability.

The successful couple, offered deference by local villagers, were defenceless in face of ugly proceedings that transcended the barriers of status and money:

The rows would be between her and my mother. Dad sat as some sort of ‘judge’ or referee and the real trouble came when Dad was away on business which happened one and often two nights a week.

Mother tried locking all the doors at midnight: Gil put her boot through the back door and tore the main bolt and lock off the door frame. That happened at least twice. The first ended with a straight fight between mother and daughter. She hit Gil, so Gil hit her back. The second my father stopped because he was there, but each time it ended with a woman and a teenage girl going to bed sobbing.

After a further court hearing in Derby, Gil was sent to an Approved School in Streatham; called ‘The Magdalen Hospital’ where she initially scrubbed floors and then looked after the younger children.

Magdalen Hospital, established in the 18th century as the ‘Magdalen Hospital for the Reception of Penitent Prostitutes’ – ‘to provide for women and girls on the streets a safe, desirable and happy retreat from their wretched and distressful circumstances’ closed in 1966.

Gil denied the rumour that she was sent away to conceal a pregnancy – for the rest of her life – but Streatham is a long way away from Borrowash; the Hospital kept no records and Robin retains doubts about a sister who was to marry but had no children:

She would never have agreed to an abortion and would have put up a huge fight against adoption – but might have lost that battle.

On 18th March, 1949, Robert Copping was declared bankrupt in The London Gazette.

The iniquitous Horsley Hall closed down as a result of a court case brought by Staffordshire County Council 1949 and on 10th April, the News of the World reported in its familiar style:

On a long trestle table down the centre of the room, ‘The Revolution of Sex’ rubbed shoulders with the English Hymnal…. The last thing I saw as I left the school was a five year old boy aiming a kick at the headmaster.

Tall, bearded Robert Copping, an apostle of self-expression in education and headmaster of a mixed ‘do-as-you-like’ school at Horsley Hall, Eccleshall, Staffs and his 31 year old partner, Edward Reynolds, were at Eccleshall, found to be unfit to have charge of children and to have kept them in detrimental environments. They were found not guilty of keeping children in unsanitary premises.

The nightmare was over and the King family resumed their accustomed upwards trajectory.

For Robertson and Dorothy, these were the glory years.

The New Year’s Honours List of 1954 saw Robertson King being awarded the CBE.

The investiture was in March and family and friends celebrated in style; relieved no doubt to be back on congenial ground.

With the Horsley fiasco now retreating into the background, attendance at the palace was preceded by dinner at The Waldorf and a memorable experience for Robin at London’s exclusive Le Caprice restaurant:

I was a very young 17 year old; seated next to Bill Bird’s daughter Jill, about 21 and straight out of two years in a very expensive Swiss finishing school. She was extremely attractive and way out of my league, so I spent most of the meal in red-faced silence. Bill was sitting on the other side of me and every time he saw my glass less than half full, he ordered another. No question of being able to put my hand over the glass with Dubonnet. I was seriously not well.

In April of the same year, it was Dorothy’s moment on centre stage. She opened the Erewash Valley Townswomen’s Guild’s exhibition of handicraft and was the subject of a rapturous write – up in ‘The Ilkeston Pioneer’.

Her opening speech was perfectly planned, beautifully spoken and had point and purpose. Nor was wit lacking.

Robin felt that this was part of a carefully orchestrated PR campaign to raise the profile of Mrs King following Robertson’s CBE; also paving the way for elevation to the promised knighthood six years later.

Meanwhile, a relatively rehabilitated Gil who had taken a first job with GK Tyre Services in Derby’s London Road (I wonder if my father’s 30 year association with Sir George Kenning had anything to do with it), had married her work colleague, Tony Williamson at Caxton Hall.

It was a marriage that suited them both, although something of a conundrum to friends:

Why settle on him?

and not Dorothy’s idea of a match for her daughter:

Gilian always picks men that need looking after – just like she was always bringing stray dogs and cats home.

Tony had a series of lifelong ailments including a dislocated hip, twisted left leg and epilepsy, but other qualities were designed to appeal to a risk-taker like Gil King:

He smoked all his life, French gauloise cigarettes and drank copious amounts of red wine and brandy…..he could start an argument in a phone box.

He was a typical jack of all trades, master of none, but a wonderful conversationalist.

It was an unconventional marriage; about as different from the union of CR and DK King as possible; which was probably the point of it.

They ran a boutique in Clumber Street during the 1970s. But it wasn’t a success because most of the profits disappeared in the costs incurred by her husband in trips to Carnaby Street to see friends and the many parties he held in the basement of the shop.

Neither was fidelity a high priority:

She wandered fairly freely, as did Tony her husband

In Gil’s case, conquests included a local journalist, various national and local footballing luminaries and work colleagues – but these did not threaten the central union.

They kept cats and dogs and Gil spoiled other people’s children.

Tony died in 1988, of a fit and heart attack, the morning after a final marital extravaganza in celebration of the couple’s 34th wedding anniversary.

Robin’s account of the funeral seems fitting:

His funeral was at Wilford Hall. He was a firm atheist and insisted on no service and no hymns. This meant that about 30 of us just stood there in silence for 15 minutes until the coffin finally disappeared. My wife got a fit of the giggles in the middle of it. Gil missed him terribly.

Life after Horsley for Robin followed traditional courses.

In September 1952, he completed his education at another boarding school; Badingham College in Leatherhead, and joined the RAF for National Service in 1955.

The Suez crisis found him keeping the aircraft records of the Valiant and Candberra bombers involved in the raids on Cairo. They used to leave their various bases in the Middle East, rendezvous over Cyprus, fly to Cairo drop their bombs and then return to base. Total flying time, about two hours ten minutes!

When he returned home on leave, he decided that National Service had some benefits:

Home on leave for Christmas, I remember going to a Derby public house, ‘The Telegraph,’ on Christmas Eve with Jim Ashton and Johnny Lees, starting a sing song which lasted about three hours, and then having to walk home from Derby because we had missed the last bus. Got in about 4 am and nobody seemed to care – one of the male benefits of National Service.

He might have been right; but it is equally likely that parents of Dorothy and Robertson King’s era turned a blind eye to behaviour from their sons that they would not have tolerated from their daughters.

But there were limits.

In 1958, when 21 year old Robin told his mother that he was thinking of spending a weekend in London with Johnny Lees, he was pleasantly surprised when Dorothy offered to book the accommodation:

My mother produced all the documents for a three night stay in London at the Corah Hotel, near Russell Square – Friday, Saturday and Sunday night – all paid for in advance.

I thanked her profusely and took the documents to Johnny, who could find no fault and was particularly pleased at how much money we had saved.

We arrived at the hotel on the Friday afternoon, just after lunch: checked in and went to our double room, with bathroom. Johnny, as soon as he had unpacked, was on the telephone asking for room service. On being put through, he asked for two large scotch and sodas, listened carefully, then put the phone down and started to laugh.

‘It’s a temperance hotel’, he said, ‘no alcohol served anywhere in it!’

Dorothy King retained her standards.

By 1959, Robin was working as an advertising assistant in the Lighting Division of the General Electric Company at its Head Office in London.

Living in the capital city might have been financially prohibitive, but again, being his father’s son came in handy.

Robertson’s appointment in 1957 as Deputy Chairman of the new Central Electricity Generating Board, based in London, made a capital city address a necessity and Robin was to reap the benefit:

Mother and Dad rented me their ‘maid’s room’ at Crompton Court, Brompton Road, SW3 for £5 per month. Just a bed and a wash basin – I used the main flat at the end of the corridor for all other living requirements.

The dawn of the swinging sixties was exhilarating for a young man with a London address – but there were drawbacks.

Girlfriends like the secretary to the MD of GEC Research and the Bluebell dancer (whose father was head of EMI Records and regularly entertained the likes of Lonnie Donnegan in the kitchen), set their sights higher than a guy with a Lambretta scooter.

Fortunately, others were more accommodating, including Melody from the typing pool who lived in Maidstone with her mother.

Matters progressed swiftly, surviving a social faux pas at the opera:

Before Christmas, Mother and Dad invited me to join them at the D’Oyley Carte’s The Mikado at The Drury Lane Theatre and invited me to bring a ‘friend’. I took Melody and we arrived late, during the Overture. Not a good start.

Worse was to come.

February 1961 brought confirmation from the doctor that Melody was pregnant and Robin finally broke the news to his mother from a call box at 10 30am one Monday morning.

Dorothy, by now the consort of Sir Robertson King was not to be thwarted:

By 11.30am that day, my phone rang and it was the Commissionaire on the GEC main entrance.

‘Mr King’, he said. ‘I have a Lady King at my desk insisting on seeing you.’

‘I’ll come down’, I said , and spent the next hour sitting in the coffee bar where I had been planning to go for lunch with Melody, getting the dressing down of my life.

For Dorothy, no doubt the think of your father’s position mindset had kicked in again – but her bark was louder than the proverbial bite.

Sir Robertson and Lady King attended the shotgun wedding on 29th March, 1961 at Kensington Registry Office and Robertson gave the couple £500 towards buying a house.

By the birth of Amanda Jane in October 1961, Sir Robertson and Lady Dorothy were proud grandparents.

Amanda was joined by Caroline in 1963 and by now, Robin and Melody were the owners of, a four bedroom semi – detached property; 65, Ashgrove Road, Ilford, Essex.

It had cost £3,500 and the couple economised by living upstairs and renting the ground floor for the first 18 months.

After the birth of a stillborn son, Nicholas, on 6th December, 1966, there were no more children.

On 1st February, 1967, Robin joined Raleigh Industries Nottingham as UK Advertising Manager.

Robin does not say how the stillbirth affected his marriage – although there seems to have been some family history of stillbirths.

Melody’s breast cancer in 1989 however, was an insurmountable trauma.

She walked out of the marriage in 1992 and died after a recurrence of the illness in 2010. Despite intermittent contact over the years; at the end, there was no reconciliation.

Mandy and Caroline (who both experienced their own dysfunctional first marriages) were extremely close to their mother and remain (wrongly) convinced that Robin had called time on their parents’ marriage.

Changes were afoot for Robertson and Dorothy.

In 1960, against his wife’s wishes, CR King signed a further 21 years’ lease on Riverside House.

By then, the indefatigueable Dorothy; increasingly plagued by rheumatism, wanted to slough off the huge responsibilities of Riverside for a more manageable cottage in the country.

It would be a well-earned rest and an opportunity to return to other pursuits such as playing the piano.

But a burglary in 1960, with thieves who were never caught, stealing £10,000 worth of Dorothy’s uninsured jewellery, made such retirement plans impossible.

Robertson signed the lease; including an onerous additional requirement to fund all necessary repairs.

Robin sums up the situation in a way that is fair to both parents:

On the face of it, the decision to sign a new lease was a smack in her face: on the other hand, what else could Dad do? He had never believed in mortgages: his age group didn’t.

A man who regularly refused to burden his company with lavish business expenses that they could well afford, was not about to burden his family with a long-term debt to a building society.

As for Dorothy – she was stuck with it.

Lady Dorothy King may have been thwarted, but there were ways of registering her displeasure and she took them.

From that moment onwards, she withdrew her all – encompassing emotional and social support from her husband’s career.

His personal files were full of copies of letters sent by his work ‘colleagues’ , like Richard Wood, Minister for Power, Sir Christopher Hinton, Chairman of the CEGB, Sir Henry Self, past Chairman of the Council, all pleading with her to attend various functions. Others were regretting not having seen her.

And without Dorothy’s shrewd business instinct, Robertson faltered:

Without her advice and guidance, he made the mistake of challenging the PM’s authority and paid the inevitable penalty

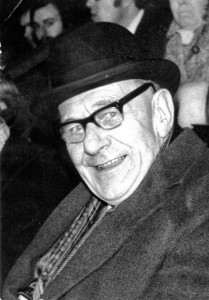

On 22nd March 1962, Sir Robertson King retired as Chairman of the Electricity Council.

It was not quite the end.

Robertson’s huge influence and contacts in the industry still held sway, and he became Chairman of Pirelli-General, the cable company, 50% owned by the GEC.

The post had formerly been filled by ex Chancellor of the Exchequer, Reginald Maudling, but the latter’s increasingly embarrassing public profile necessitated a safe pair of hands.

These wee Robertson King’s and Robin’s father held the position for three years before being succeeded in turn, by another former Tory Chancellor, Peter Thorneycroft.

The Kings gave up their London flat and concentrated their efforts in Derbyshire where as usual, there was plenty to do.

Robertson became increasingly involved with the fortunes of Derby County, becoming its President, with benefits to all the family.

Comedian, Eric Morecambe was a close friend. Whenever, he was booked to appear at the Hippodrome, he made time to watch Derby County and Robin recalls sitting with Gil in the Director’s box in 1975.

Beside them was Eric Morecambe, in guise of ‘Mr Bartholomew, Chairman of Luton Town.’

Robertson had a ringside seat (and an active role) in the controversies surrounding Brian Clough and Sam Longson, and today, his son Robin, is still assembling papers and letters for eventual publication about a roller-coaster period in the life of Derby County Football Club.

But in the long and complex saga of Robertson King’s life, his son’s brief diary entry puts matters in context:

15th October, 1973: Brian Clough and Peter Taylor at Riverside, trying to negotiate a deal with Dad to take over Derby County.

Failed.

After a period of ill health dominated by prostate problem, Robertson King died at Riverside as he would have wished, on 16th August, 1976. He was cremated at Wilford Hill after a funeral at St Mary’s Ilkeston.

He had not left a formal will and Robin recalls:

The only will we could find was scrawled on a bit of paper, torn from an exercise notebook which read: To Whom It May Concern – I leave everything to my wife. It was dated February, 1942.

He apparently wrote that whilst lying underneath a bed during a pretty bad air raid at the Waldorf Hotel.

Robertson King, a staunch Conservative who had time for neither Harold Macmillan nor Ted Heath, had ironically, prospered under Labour Governments.

His death in 1976 meant that he did not live to see the reign of Margaret Thatcher although, age permitting; he would doubtless have continued to thrive.

Dorothy King, who was assuredly the best business partner he ever had; died in a residential Care Home in 1986.

After the death of Tony and the failure of his own marriage, Robin became closer to Gil; visiting, talking and holidaying together in San Francisco in 2004.

Her death in 2008, from multiple organ failure after an emergency operation in the Nottingham Queen’s Medical Centre for a blocked gut was as unexpected and brutal as Tony’s had been in 1988.

Robin’s account captures the horror:

She never regained consciousness and her kidneys, one lung and her heart, were all machine-assisted when she came out. On the Wednesday morning, they asked my permission to turn off the machinery as she would not survive – particularly as her right leg had gone black from toe to hip and would have to be amputated , which she would not survive,

I gave my permission and left. They called at 2pm to say she had died some 30 minutes before.

His last words to Gil, as she was wheeled into the operating theatre, were to offer reassurance that her dogs and cats were being looked after.

The life of Robertson King is a very 20th century story.

From ‘comfortable’ but certainly not ‘lavish’ origins, he scaled the heights of British industry, thriving under Governments of both political persuasions; rubbing shoulders with Prime Ministers, celebrities, sporting and media stars.

At the same time, a propensity to make family decisions in accordance with social status and the received wisdom of the era meant that he was at times, dangerously blind to the needs of his own children.

In this, he was unconsciously abetted by Dorothy, an assiduous mother, ambitious wife and talented woman in her own right, whose concern for her husband’s position led her to misinterpret the experiences of Robin and Gil – most disastrously in the Horsley Hall fiasco.

As Robin, reflects upon his life and that of his sister, he concludes that in their various ways, they both disappointed parents that they nevertheless, respected and revered:

Over-achieving I would have welcomed – but even then, it wouldn’t have come near to satisfying or excelling Dad. Trouble was, he was friends with the original Lord MacAlpine, who had three sons, all of whom were as successful as him. He was also a friend of Lord Robens, whose son, another Alf, horrified his father by opening an advertising agency in Nottingham.

In a new century, there are outstanding questions that will remain unanswered for the King family – but avenues to understanding are closed, like the doors of Riverside House and they belong to an era that was liberated and inhibited in equal measure.

Did Gil have a baby – a cousin for Mandy and Caroline, who might yet be alive?

Was Gil right in thinking that her mother too, had an active secret sexual life away from the constraints of ‘Lady King’.

Was Melody’s real mother, in fact, her Aunt Jill who also had breast cancer?

The answers remain behind closed doors, and as Robin says:

Now we’ll never know – and perhaps we shouldn’t.

He has a point; but as with so much of the King story, perhaps the last word should remain with Gil who was accustomed to say in face of life’s roller-coaster:

Ain’t life grand, played long?

4 Responses to Behind Closed Doors – Robin King